In 1985, a decision was made by the Hawke Labor Government to return Uluru, previously known as Ayers Rock, to the traditional owners, the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara people. I was fortunate enough to be there on that day.Stepping onto the tarmac at Yulara airport was an entry into another dimension. Bathed in the warmth of the October sun, there was immediate comfort, an affinity with the colour and clarity of light, and an inexplicable feeling of having been there before. We were bussed into Yulara village, the multimillion dollar resort still under construction to serve the tourist industry, and assembled at the Sheraton hotel. (Little did I know that just five years later I would be selling magnificent Aboriginal artworks from this same hotel).From the Sheraton a large ensemble of people gathered, and eventually a much larger bus cruised the forty kilometres out to Uluru, which dominated the landscape from Yulara, and grew in stature and power as we approached.The return of Uluru to the traditional owners was to take place at the Mutitjulu community, nestled in the bush on the far side of the rock from Yulara, and the original site of the early tourism development before the Yulara resort was mooted. This was also the site of a couple of infamous incidents – one being the crazed truck driver who drove his semi-trailer through the bar of the Outback Hotel after an altercation with some drinkers, killing several people around the pool table. The other was the disappearance from the camp ground of the baby Azaria Chamberlain in the jaws of a dingo, and the consequent controversy. At the time of my arrival at Yulara, Lindy Chamberlain was serving the second year of her life term in a Darwin prison, and in the Northern Territory at that time, life meant life. After three years, she was released amid much controversy and a after a number of enquiries, she was totally exonerated.

There were black faces from all over Australia to celebrate this historic occasion, as well as many white supporters of the Pitjantjatjara and Yunkinjitjara people, who still held the ancient stories of Uluru in their hearts and minds. The Federal Labor Government under Prime Minister Bob Hawke had initiated the return of Uluru in the spirit of natural justice and land rights, much to the disgust of the conservative Northern Territory Government, who not only boycotted the ceremony, but withdrew the Northern Territory Conservation officers from their long established relationship with the Uluru/Katatjuta National Park, a decision they would regret in due course.

Because of the short-sighted attitude of the NT Government, the ceremony on that day would entail the official hand-over to the traditional owners by the Governor General, Sir Ninian Stephens, to be followed by the signing of a ninety-nine year lease agreement to the National Parks and Wildlife Service, the Federal Body which would take over the management of the park, with traditional owners maintaining a majority management role on the Park Board. There was other opposition to the ceremony within the Australian community, mainly from those ignorant of Aboriginal relationship to land, but also from opportunistic racists.

The gathering of people on the red earth that day, with the Rock providing a magnificent backdrop to the official table, had no thoughts of opposition to the anticipation and excitement which was building up as the official party’s arrival drew near. I noted a space to the left of the table, which would enable a close view of the ceremony for photography , and settled there, bathed in warmth, comfort, and a great sense of the occasion. Oblivious of the import of the day, some camp dogs settled in the shade of the table, and slept soundly.

Looking back on the photographs I took that day, it is clear that the majority of the crowd were looking at the ceremonial table, on a rise, with Uluru behind, with the sun almost directly in their eyes – unfortunate for them, but great for the photographic record I was able to take. The official party entered the area from my left as I looked down, crossed to their seats at the right hand side of the table, and in a state of great excitement, the ceremony began. The main protagonists were the Governor General, the Federal Minister for Aboriginal Affairs Clive Holding, Environment minister Barry Cohen, and the chair of the Pitjantjatjara Council, Yami Lester, who was blinded as a young man in the era of nuclear bomb testing at Emu fields. Yami, in spite of his blindness, had taken advantage of his time in Adelaide when his blindness struck, to get a good education, and it was as an eloquent speaker of English and Pitjantjatjara that he was to play the role of interpreter for the benefit of the many bush people in attendance.

The ceremony was conducted with great dignity and gravitas. In reference to opposition to the hand-over, Yami joked that ‘some people seem to think that the Rock will not be here tomorrow, that it might be towed away…..’

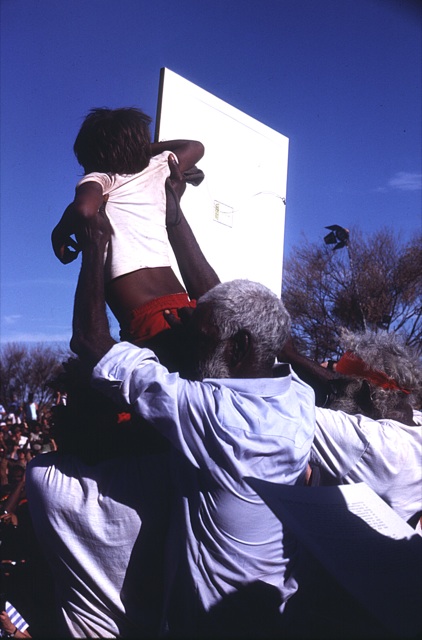

Sir Ninian spoke with eloquence, pausing for Yami to interpret. He spoke of Uluru being ‘not only the physical heart of the country, but the spiritual heart…..’ The ceremony proceeded, with great excitement building, until with an overwhelming sense of euphoria, the framed, glass-encased certificate of ownership was passed to the traditional owners, who held both it, and a small child, above their heads to the delight of the crowd.

At the height of these celebrations, a light plane flew directly overhead, trailing a giant sign which read, ‘AYERS ROCK FOR ALL AUSTRALIANS.’ It was a well timed but futile gesture, which underlined the presence of many in the population adverse to any recognition of Aboriginal rights to their land and culture. For precious moments the Pitjantjatjara were the sole, unencumbered owners to their land. Their signatures on the lease agreement which followed, many of which were simple crosses, set in place what has proved to be an extremely successful formula for the management of the park.

There ought to be no illusions however, about the standard of living within the Mutitjulu Community, which, despite a certain amount of financial benefit from park income, has not substantially changed the poverty stricken, petrol sniffing, and violence-ridden settlement. It is the starkest of contrasts to the multimillion dollar swimming-pooled, air-conditioned, restaurant-dotted luxury on the other side, all generated by the tourist industry, privately owned, outside the park, and with not a black employee in sight.

The afternoon concluded with some traditional dance, and a barbeque. We were bussed back to Yulara Village, and my initial introduction to the red centre had begun in spectacular style.